I was stuck a few months ago. After the unexpected but welcome blessing of the birth of our healthy newborn (the two older kids are 20 and 18 😊), my wife and I had just come home from the hospital following emergency surgery resulting from latent labor complications.

We had a plan worked out for the division of labor with the baby’s homecoming, but that plan evaporated after my wife’s emergency surgery. Now, we had a newborn and a recovering patient. Whatever was coming next was on me.

In a moment of not-so-quiet desperation, I confessed to my wife, “I’m just not made for this. I can’t do this.” This limiting belief led me to seek out confirming evidence of my inability to act effectively and resulted in momentary paralysis when my family needed me the most.

This conundrum is especially noticeable in the realm of personal finance, where “I can’t do this!” is thrown around about everything from taxes and estate planning to insurance and investing but may be most evident in the aversion to a single word: budget.

To be fair, the financial industry, the legal and accounting worlds, and the politicians who make the laws with requirements for nearly everything with a dollar sign attached to it haven’t made it easy on us. If anything, the intersection of these bodies creates a complexifying dynamic that tempts us to throw up our hands in frustration. But when we allow that frustration to devolve into believing that we’re incapable of effective financial planning, we only undermine ourselves.

Financial failure becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

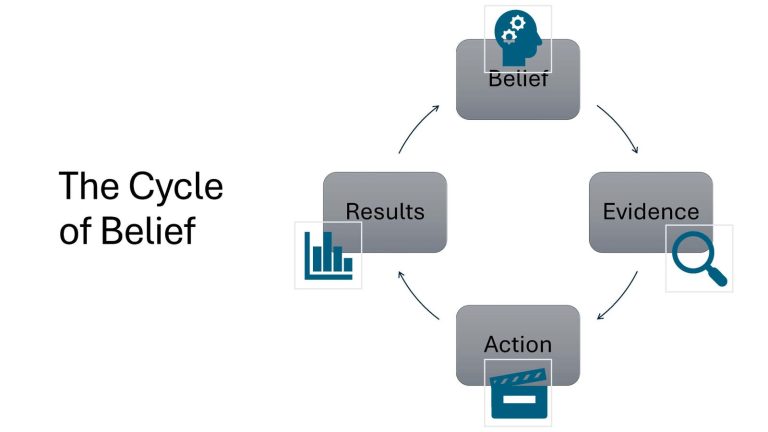

Consider this simple visual to explain how we often trip ourselves up, a concept that was recently illuminated for me by Sandler consultant, Mark McGraw:

Here’s how it works. We naturally arrive at all sorts of beliefs and judgements that often originate on an emotional, even subconscious, level, rather than rational. Whatever our belief, we’re inclined to seek out evidence that supports it—a phenomenon dubbed “confirmation bias” by behavioral economists. A confirmed belief is a powerful force for action consistent with that belief, and results flow from our actions.

But what if our belief is foundationally flawed? Again, failure becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The mistaken belief that I couldn’t successfully navigate basic caretaking duties for my wife and newborn ultimately led to an unacceptable result. So, how do we rewire our thinking?

Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel-prize-winning researcher, has likely done more to elucidate our understanding in this arena than anyone. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, he writes, “The confidence that individuals have in their beliefs depends mostly on the quality of the story they can tell about what they see, even if they see little.”

Therefore, we may have to change the story we’re telling ourselves to improve our outcomes. After my moment of self-pity, I first needed to face reality: My wife was incapable of partnering much in this early-parenting endeavor and needed a great deal of support herself. And we had a newborn that required a great deal of care. Those were the facts.

Caretaking felt foreign to me because I’d never done it before, and I hadn’t held a newborn in 18 years! But I had several pages of nurse’s instructions for my wife and a book entitled, Moms On Call: Basic Baby Care 0 – 6 Months, a manual that I implore you to get your hands on if you are a new parent.

These resources gave me a game plan for the basic levels of care for which I was responsible. For anything beyond the basics, I had professionals at my disposal—my wife’s OB/GYN and the baby’s pediatrician—not to mention two grandmothers and a community of support that extended well farther than I had initially imagined.

I remember right where I was (on a long walk with my sleeping daughter) when it hit me, and I converted the script in my mind from “I can’t do this” to “I can absolutely do this,” a refreshing new message that ultimately led to an even more confident, “I can do this well.”

So, what are your “I can’t do this” areas in financial (or other) matters? What beliefs might you consider questioning? What stories need retelling?

What are the basic elements of financial planning for which you must be held responsible—and what areas may you need a professional to partner with on your journey?

Interestingly, the most common “I can’t do this” I hear is also the most basic: budgeting, or the more enlightened, cash flow management.

I know budgeting isn’t easy, per se, but it is simple. These are the table stakes of personal finance that no one else can do for you. Yes, there are a host of apps (and I’ll be doing a roundup of the best-of during Financial Literacy Month in April), but technology and even AI still can’t force you to examine your spending, to project what you plan to spend, and most importantly, to stop you from overspending.

Oh, by the way, you can master budgeting and find a cash flow system that works for you. I promise. (And I’m only allowed to use that word in the rarest of circumstances.)

Then, beyond the basics—and your areas of competency—have you gotten the help you need? Unfortunately, even the foundational building blocks of wealth management—like investing, tax, estate, education, insurance, and retirement planning—are fraught with complexity and seem ever-changing.

The good news is that you don’t have to become an expert in any or all of these areas, but you do need to address them and solicit help where necessary.

We are each uniquely gifted in different ways, but one thing we all share in common is a tendency to amplify and excuse our less helpful thinking and behavior. The cycle of belief helps us address and overcome this challenge.

Read the full article here